Linns and Grahams

The first record of our Lynn relatives in England, in fact the first record of any of our ancestors, was the marriage at St Gregory’s Chapel, Whitehaven on Saturday, 1 February 1845 of James Lynn (Catherine’s brother) a cooper of Tangier St to Ellen Magahan.*

The marriage certificate of Andrew Graham and Catherine Linn, my great, great, great grandparents, reveals that Catherine’s father, James Linn (great, great, great, great Granda), was a coachman in Newry, the town which straddles the county boundary separating County Armagh from County Down and that Lawrence Graham, of Co Louth, was a weaver.

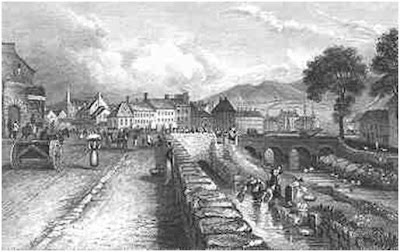

Newry from an old print, with women washing clothes in the canal. The Newcastle [upon Tyne] Courant reported that a hurricane had driven the sea to breach the banks of the canal in October 1844 causing serious damage.

The Tithe Applotment Survey records a James Linn in the townland of Edingarry/ Edenagarry, Ballybrick division, civil parish of Drumaballyroney in 1827. Similar details were recorded in 1837. Drumballeyroney is immediately east of Newry. The catholic parish is Annaclone, St Colman’s Parish church. Baptism records there date from 1834 and marriages from 1836. As Andrew was born around the year 1826, there would be no record of his birth at St Colman’s I am trying to find out which church served the area in the 1820’s.

*It’s tempting to speculate whether Ellen was a Monaghan, and one of our Monaghans at that, but there is no evidence to support this.

Newry Town Hall.

Newry, Co Down, by Frank McKelvey RHA (1895-1974)

This map shows the town of Newry in Northern Ireland, home of the Linns, and Co Louth in the Irish republic, home of the Grahams.

The Linen industry

Andrew Graham’s father Lawrence (my great, great, great, great Granda) was a weaver in the neighbouring County of Louth. Flax was a major product in Louth, so we can assume that Lawrence was weaving linen.

‘Retting flax was a smelly, but essential part of the process of linen production! The objective was to rot away the soft vegetable matter leaving the tough fibres to be turned into linen.

Flax was a beautiful crop and its feathery growth had, from any distance, a limped greenness that moved fluently in the slightest wind and became the background to a marvellous blueness when it flowered. There were few flowers to be seen in our district of tiny farms and no gardens, where all vegetation was green sprinkled with white or pink blossom on the bramble and thorn and wild fruit trees, and these sudden rich bluenesses seemed extraordinary in that landscape, exotic and unnatural. The flax had to be pulled by hand, since it grew mingled with thistle and weed, so harvesting it was a painful and backbreaking business. After it was pulled, it was put to soak in the flaxholes that lay festering and stagnant in the corners of the low-lying fields, surrounded by the heavy stones which held it under water. When the flax had rotted – or retted – in the holes for a month or more it was lifted out slimy and foetid, and spread on smooth pasture to dry, and its strange sour stench hung across the countryside. You could almost see that smell, vaporizing and shimmering acidly over the fields.’ (‘All of Us There’, Polly Devlin)

Hand weaving linen. This was Andrew Graham’s occupation.

‘Every part of the process of making linen out of flax was tedious and fraught, and even, in the system of scutching – the crushing of the fibres by rolling and beating – dangerous, since they had to be held in the hand against spindles rotating at high speed; many a man lost more than a crop.’ (‘All of Us There’, Polly Devlin)

The finished product, linen cloth, being bleached in the sun.

‘When the linen was woven it was pale brown, or greyish brown, not white at all, and it was stretched on smooth pasture to be bleached by the sun and the weather.’

(‘All of Us There’, Polly Devlin)

An Early Graham Marriage in Whitehaven William Graham, a miner, of Croft Pit, ‘of full age’ son of John Graham, a husbandman, married Catherine Hickey ‘of full age’ of Croft Pit, the daughter of Dennis Hickey. The marriage took place at the parish Church of St Bees on 18 February 1843, the witnesses were Edward and Eleanor Henderson - Catherine’s hosts at the Croft Pit in 1841 where Edward was the engineer The couple’s daughter Mary Ann was baptised at St Begh’s on 23 December 1847, the sponsors were James Hickie and Catherine McManus (info from Maude Smith, Parish Sec. St Begh’s) |

As mentioned above, Catherine and Andrew married at St Gregory’s Chapel (later St Begh’s Priory), Whitehaven, on Thursday 20 May 1847. Andrew Graham, aged 21, was a labourer and Catherine Linn a servant. The witnesses at the wedding were James and Nancy McCann of Whitehaven. In those days witnesses at weddings, and sponsors at baptisms were often relatives. It’s possible that the McCanns were related to either Andrew or Catherine.

Another view of St Gregory’s where numerous

Grahams were baptised and married.

Mary (my great, great gran), the first child of Andrew and Catherine Graham, was born on Saturday 19 August 1848. Andrew, previously a labourer, was working as a miner; this was to remain his occupation. The family were at 20 Peter Street, Whitehaven. Mary was baptised at St Begh’s on 20 August 1848. Andrew and Catherine’s first son James was born on Saturday 20 April 1850 at 6 Wellington Row, and baptised the following day. His sponsors were his uncle Patrick Graham and Margaret Dixon.

Andrew’s brother Patrick Graham, 22, a coal miner, born Ireland, appears on the 1851 census. Patrick was a visitor at the house in Scotch Street of another Irish miner, Bernard McClean. Later that year (29 August) Patrick Graham, son of Lawrence and Mary Graham of Whitehaven, married Catherine ....* This information from the records of St Begh’s Priory tells us that Patrick and Andrew’s mother was called Mary, and that she and Lawrence had moved to Whitehaven. This has just come to light and I will do more research in Whitehaven to see if more can be discovered about Lawrence and Mary Graham. Patrick’s bride, Catherine McAtee* lived with her parents Edward and Elizabeth at Bacon Court Tangier St. Edward was an ‘infirm pauper’, her four brothers were coalminers and Elizabeth was an envelope maker. Mary Ann Pye, Catherine’s bridesmaid, was the wife of a miner of Temple Lane off Catherine Street. The other witness was Robert Martin, a coal miner who appears with his family at Castle Row on the 1861 census. Patrick and Catherine’s children were named after their grandparents in the traditional manner. Elizabeth, their first child was born in summer of 1852, but no details of her baptism are available. In a departure from the traditional naming pattern, Patrick and Catherine Graham’s second son, John was born in 1859. At his baptism on 13 July 1859 the sponsors were James Crangle and Elizabeth McAtee. James Crangler seems to have been a 13 year old cotton labourer of Ginns Back Street. He was the son of John, born in Ireland, and Margaret, born in Scotland, their son was born in Ireland, there seems to have been similar travel between Ireland and Scotland in the Lynn family. Edward was named after Catherine’s father, at his baptism in 1862 his godmother was Isabel Martin (a relative of Edward’s parent’s best man?), the other sponsor was John Kennedy, there were several Irish John Kennedys in the 1861 census, and at this stage it is not possible to identify which was Edward’s godfather. Patrick Graham died of chronic bronchitis in December 1865, at Peter Court, Peter Street, Whitehaven. James was 36 years old and was a coal miner; the informant was Mary Cherry, of 7 Peter Street, the Whitehaven born widow of a labourer. Catherine, a widow, appears on the 1871 census. The family was at Brigg’s Court, just off Peter Street. Catherine’s daughter, Mary Graham (14) was, like her cousin and namesake a worker in a thread factory. John at the age of ten was a ‘coal pit boy’. *The BDM website records Patrick’s bride, Catherine’s surname as McFee, the St Begh’s church secretary transcribes the register entry as McKee, subsequent baptisms entries in the St Begh’s marriage register are transcribed as McTee and McAtee. Ancestery.com indexes the family’s surname as McAbee, but the entry clearly reads McAtee, a sponsor at the baptism of Patrick and Catherine’s son John was Elizabeth McAtee. |

On Saturday, 4 March 1854 Lawrence Graham, was born at Bacon Court, Tangier Street, Whitehaven. He was named after his grandfather, Lawrence Graham, and Andrew Graham, his uncle,Patrick, was one of the sponsors when he was baptised at St Gregory's. The other sponsor (godmother) was Margaret Morgan an Irish girl who lived with her parents at Jellack[?] Lane. Her father was a miner and her mother, like Margaret was a domestic servant. Lawrence does not appear on the 1861 or any subsequent census, suggesting he died in infancy, though if so his death does not seem to have been registered.

Mary Jane Graham was baptised in 1857. Her name raises the question, was Lawrence Graham senior’s wife Mary or Mary Jane? Mary Jane’s godfather was Hugh Morgan, a young cartman (14) whose family had arrived from Ireland via the Isle of Man where he and two of his siblings were born. In the Morgan household was a 70 year widow, Margaret Convey, ‘house servant’ likely a relative. Or less interestingly Hugh Morgan (28) a general labourer. Lodging at Patterson’s buildings. The other sponsor was Elizabeth McAtee.

The Lynns

Catherine’s brother James Lynn appears on the 1851 Census in Tangier St Whitehaven. The census records the fact that he was born in Scotland, so James Lynn and his wife must have spent time in Scotland around 1823-25. Despite checking the records twice I have been unable to find Andrew and Catherine Graham and family on the 1851 census, I wonder if the family had returned to Ireland for some reason.

The Grahams were certainly in Whitehaven on Friday, 19 March 1852 when Andrew Graham was born at Banks Lane, George Street. Perhaps Andrew was in some danger, as he was baptised the day he was born with just one sponsor, Alice McDoughal.

Eleanor Graham was born at 9 Temple Lane, off Catherine Street, on Wednesday 24th May 1854. Her sponsors were Edward and Catherine McGee. She was baptised the day she was born, but Catherine did not report the birth until 13 June. Patrick Graham was born around 1857, but he was not baptised at St Begh’s, so the place of his birth, given as Whitehaven on the 1861 census, is a mystery. Thomas Graham was born at 2 Temple Lane on Friday, 4 November 1859, sponsor Margaret McGee. (In 1881 Margaret McGee was lodging with her sister, Catherine McCann - sponsor at the baptism of Eleanor Graham in 1854.)

Whitehaven was laid out in the 18th century on a grid plan by Viscount Lowther (the local landlord and coal owner). However, in the expansion of the industrial revolution Whitehaven had become a terribly overcrowded town, the original streets supplemented with courts and closes. A Mr Rawlinson, reporting on the state of the town in 1849, found in street after street ‘scenes of utter destitution, misery and extreme degradation', with pigs being kept in many of the town’s cellar dwellings alongside the people, and the conditions of many of the poor inferior to those of the prisoners in the town goal.

In 1861 (at the time of the census of 7 April) Andrew and Catherine and the six children were living at 2 Temple Lane, off Catherine St, Whitehaven. Mary, aged 12, was working in a thread mill, possibly one of the 100 employees at James Wilson’s Thread Mill. Andrew, her father, was working in one of the pits of Whitehaven, the deepest in the world at the time, as was his 10 year old son James. James should only have just have started work as the Coal Mines Act of 1842 forbade the employment underground of anyone under 10 years of age. James was employed as a trapper, which meant that he would sit in the dark for up to 10 or 12 hours a day ready to open the door when the pit pony arrived pulling its load of tubs of coal, then shutting the door behind it. The trapper's work was essential to ensure a circulation of air that would suck fresh air into the pit, and flush out the foul air and gas that might be building up ( the Whitehaven pits were notoriously gassy, or ‘fiery’). In 1849 trappers were being paid 9d or 10d (old pence) a day for a twelve hour shift.

The next record of the Grahams occurs a decade later when there is the first record of them in Durham. They have yet to be found on the 1871 census; I have checked the Whitehaven returns, and they don’t appear to be included - perhaps they were already in Durham.

No comments:

Post a Comment